British Columbia’s Vancouver Island is a geologically complex isle, a little bigger than Sicily, half-tucked into a Pacific Northwest pocket on the west side of North America.

Tectonically, it is surrounded by the active boundaries of three tectonic plates – the North American, Pacific and Juan de Fuca, and the Cascadia subduction zone. All are prone to volcanic and earthquake activity, making it easy to imagine a geological history that includes volcanoes, mountain folding, earthquakes, tsunamis and other tectonic events. Add in periods of ocean submersion and resulting marine sediments, glaciers, and morainal deposits, and the extensive diversity of soil types, slopes, altitudes, and prospects in Vancouver Island’s geography is no mystery.

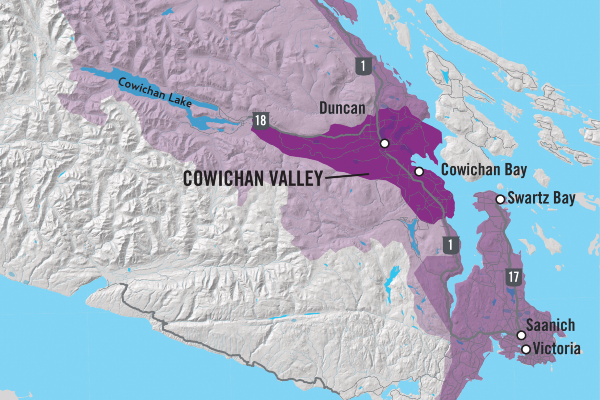

The Cowichan Valley sits in the Southeast corner of Vancouver Island, south of Vancouver, not far from the Salish Sea - centred about the 48th parallel one degree south of the Canada/U.S. border.

The climate is classified as maritime Mediterranean. It sits in the rain shadow of the Vancouver Island Range, one of the protective necklaces of mountains that run along the center of Vancouver Island. Though a decidedly cool climate, the average temperature in the Cowichan Valley is one of the highest in Canada. It has a long frost-free growing season, and the rain that does fall is mainly in Winter.

Cowichan Valley Sub-GI

The Cowichan Valley was the first region outside the Okanagan Valley to be recognized as a sub-GI in June 2020. It has grabbed our attention for its high-quality pinot noir production.

The 350 square kilometre Cowichan Valley Sub-GI surrounds the city of Duncan. It extends from the coast between Maple Bay and Mill Bay (in the east), along Cowichan River to Cowichan Lake (to the west) and as far south as the village of Cobble Hill. The vineyards range in elevation up to about 250 meters. Virtually all the fourteen Cowichan Valley wineries have some pinot noir planted, and ten consistently produce still red pinot noir. Numerous sparkling pinot noirs and rosés are also made. The total pinot noir vineyard area of pinot noir is presently boutique level, about 25 hectares, though more is coming fast.

The commercial era of wine production in the Cowichan Valley dates to the very early nineties, but a confluence of people and events in the last ten years, combined with the uniqueness and excellence of its cool climate pinot noirs, the area is beginning to receive the wider recognition it deserves.

Some of the first pinot noir vines were planted in and around 1990 at Venturi-Schulze Vineyards, Blue Grouse Vineyards, Zanatta Winery (then Vignetti-Zanatta) and Alderlea Vineyards. For a wine industry that is only thirty years old, having the right grapes in the right vineyard sites initially is crucial because, despite thorough research beforehand, there are no guarantees that a particular grape variety will thrive and produce superior wine there. Fortunately, many pioneers guessed right when they planted pinot noir in the Cowichan Valley.

Wineries such as Glenterra Vineyards, Zanattta Winery, Averill Creek Vineyard, Alderlea Vineyards, Emandare Vineyards, and Venturi-Schulze Vineyards all have older pinot noir vines that helped set the baseline for the grape in the valley.

Stephen Spurrier, the celebrated English wine writer whose “Judgement of Paris” tasting in 1976 showed that great wine could come from other wine regions (California), not just the hallowed vineyards of Europe. In his keynote speech at the B.C. Pinot Noir Festival in 2016, he said that – wine is all about the three p’s - people, place, product and it’s increasingly apparent over the last decade that all three are present in the Cowichan Valley.

Progress is often an accumulation of small things, but it can make an appreciable difference when you are this small. The nature of wine is that it touches and depends on numerous factors that find their way into the final liquid in the glass. The past decade in the Cowichan Valley has brought pinot noir to the fore. Some of these changes could be more expected, i.e. increasing vine age, a maturing industry where techniques become increasingly shared and new technology.

The GI and Sub-GI framework rightly brings attention to the importance of place in understanding wine. But ultimately, at the vineyard level, the right grapes in the right place, tended by the right people, can make magic happen in your glass. Under the “People” heading of Spurrier’s list, it’s worthwhile to note a few of the Cowichan Valley pioneers who set forces in motion or helped move the dial for pinot noir.

Emandare: Fleurie Vineyard a 3.5-Hectare Adventure

Planted in 2001, the Fleurie vineyard North of Duncan supplied high-quality pinot noir and other grapes to wineries as far away as Saanich through to 2011. At that time, it was essentially abandoned by its grower/owner.

In 2013, after a province-wide search, Mike Nierychlo and his wife Robin began their “3.5-hectare adventure” in the Cowichan. A faithful, passionate advocate of low-intervention winemaking and nurturing vineyard soil, all his wines, led by pinot noir and sauvignon blanc, have moved from strength to strength in the decade since they began.

Venturi-Schulze: Never Too Old to Learn

Giordano Venturi, the talented, eclectic, inventive founder and winemaker at Venturi-Schulze, has always been one for learning and adapting. From diesel electric maintainer to a degree in education to teaching electronics to designing hardware and software systems, he has a track record of remaining open to and learning from the new. After twenty vintages or so at Venturi-Schulze, for four years, as he found time, he pursued a Master of Wine course in part to travel to other wine areas and be exposed to different wine-making ideas. He brought that experience back to inform his winemaking, notably to his much-improved estate pinot noir.

Averill Creek Vineyards: Onward and Upward

Established in 2001 to make Canada’s best pinot noir, Averill Creek has produced remarkably consistent, fine-quality estate and reserve pinot noirs that almost single-handedly established the reputation for the grape in the Cowichan Valley, especially between 2006 and 2014. Winemakers naturally influence the style, quality and ongoing dreams of a winery and its wines. They can bring with them accumulated experience, fresh ideas and new perspectives. In 2018, the dedicated owner Andy Johnston engaged Brent Rowland, who brought with him an impeccable pinot noir winemaking resumé that included stints in top wineries known for their pinot noir in Australia, California, New Zealand, Niagara and France. He favours whole cluster fermentation for pinot noir, has introduced concrete fermentation vessels, reduced fining and filtering and a range of winemaking/elevage techniques, seeking to take Averill Creek to the next level.

Alderlea Vineyards: Changing of the Guard

Zac Brown and Julie Powell purchased the meticulously tended Alderlea Vineyards in 2017 from one of the valley’s pioneer pinot noir winemakers, Roger Dosman, who was retiring from the business. Both left corporate careers to pursue their dream of a small, quality winery based on standard organic practices. Though not formally trained, they share the winemaking, and both have won national awards for their wines. The vineyard sports a diverse cover cropped, pollinator-friendly and no tilling. To the typical Cowichan Valley mix of pinot clones such as 113, 115, 667 & 777, they also grow two thicker-skinned Alsace clones, 538 Colmar and 93, that help create darker, more decadent pinot noir that nevertheless remains supple. Mostly self-taught but with a background in chemistry and biology, Zac became, in his words, “a nerdy Garagiste home winemaker for two decades & taught winemaking online for ten years.” The results are evident in his pinot noirs' developing complexity and poise.

Saison Vineyard: Chef Meets Baker

Not all vineyards are part of the estate holdings of a winery. Grower-only vineyards also have a role in most wine regions, supplying grapes, often under contract to the wineries there. The availability of Saison Vineyard pinot noir fruit beginning about ten years ago in the Cowichan Valley proved a well-timed to move a level up in pinot quantity and quality in the valley.

wineries there. The availability of Saison Vineyard pinot noir fruit beginning about ten years ago in the Cowichan Valley proved a well-timed to move a level up in pinot quantity and quality in the valley.

Frederic Desbiens, the chef and Ingrid Lehwald, the baker, met in White Rock one day when Frederic was trying to source some bread and stopped at her bakery. Jump to 2009 when the couple began planting the Saison Vineyard in Cowichan Valley, where Ingrid was raised. Dry-farmed, the vineyard is planted at a higher density (about 50% greater) than a typical North American site to have higher yields in the same area and produce more concentrated flavours. Frederic and Ingrid are dedicated farmers who work the vineyard meticulously and mostly themselves. Frederic calls it “attentive farming.” The plant responds to the growing season, and they react to it.

By 2012, Saison was beginning to sell pinot noir grapes to a handful of wineries that would eventually include Unsworth Vineyards, Blue Grouse Vineyards, Rocky Creek Vineyards, Rathjen Cellars and Alderlea Vineyards, all on Vancouver Island, as well as Domaine Jasmin on Thetis Island and Vista D’Oro in the Fraser Valley.

The timing could have been better for Unsworth (recently launched) and Blue Grouse (who had just changed hands), who had plans to expand their pinot noir offerings but had little estate pinot noir themselves. They began using Saison pinot noir fruit to increase their case volume. Since then, Saison fruit has been a component in most Unsworth pinot noir bottlings and the Blue Grouse Quill pinot noir. It importantly meant they needed less to seek pinot noir fruit from outside sources before the Sub-GI implementation. It enabled them to move towards wines with 100% Cowichan fruit.

The additional volume of pinot noir fruit was welcome, but the exceptional quality of Saison pinot noir grapes also became apparent when, beginning in 2014, the pinot noirs started winning medals. Unsworth, mainly, ended up winning a string of them. In Canada’s 2021 Wine Align National Wine Awards alone, pinot noirs partially or entirely Saison fruit garnered a Platinum for Rathjen Cellars, a Silver and Bronze for Unsworth and a Bronze for Blue Grouse.

But the biggest splash in the wine award world was at the Decanter Magazine World Wine Awards 2021 when the Unsworth 2019 Pinot Noir containing Saison fruit earned 91 points and a Silver Medal. This was the highest score ever for a Vancouver Island wine and one of only a handful of Canadian Pinot Noirs to get 90+ points overseas.

Unsworth Vineyards: Not the Type of Guy to Sit On the Beach

Tim Turyk had retired from a long career in the fishing industry and was vacationing near the Cowichan Valley in 2009. He made an offer on a piece of land he had spied on, and his let’s-build-a-family-winery retirement project began with his son Chris as overall manager. The winemaking at Unsworth has been ably helmed since 2015 by cool climate specialist Dan Wright, who worked vintages in the Niagara Peninsula in Ontario, Orange in Australia, Marlborough, New Zealand, and the Willamette Valley in Oregon. Since it began, the winery’s reputation has grown via a range of impressive wines, including whites, sparkling, rosés and reds. On the pinot noir front, early on, they were able to supplement their two acres of estate pinot noir with Saison fruit - a great piece of luck.

and his let’s-build-a-family-winery retirement project began with his son Chris as overall manager. The winemaking at Unsworth has been ably helmed since 2015 by cool climate specialist Dan Wright, who worked vintages in the Niagara Peninsula in Ontario, Orange in Australia, Marlborough, New Zealand, and the Willamette Valley in Oregon. Since it began, the winery’s reputation has grown via a range of impressive wines, including whites, sparkling, rosés and reds. On the pinot noir front, early on, they were able to supplement their two acres of estate pinot noir with Saison fruit - a great piece of luck.

The wine world eventually took notice. In June 2020, Unsworth was sold to Americans Barbara Banke and Julia Jackson of giant Jackson Family Wines. As admirers of what Unsworth was doing, they left the entire management and staff in place, bringing instead financial resources and industry expertise to extend and deepen what the winery was already doing. Their new vineyard plantings alone could see total pinot noir acreage in the Cowichan Valley increase by fifty percent.

Blue Grouse Vineyards: Changing of the Guard Twice

Blue Grouse, the second Vancouver Island winery to receive its license, was begun by Dr. Hans Kiltz in 1992, and he made pinot noir as part of his lineup. It was subsequently purchased by Paul Brunner and his family in 2012. The winery was revitalized under the “Blue Grouch,” as Paul Brunner called himself. He was thinking big, as the effort included building a spectacular new winery tasting room and accommodations and two rounds of new vineyard plantings, including pinot noir. The winery became a real Cowichan Valley destination. The years since have also contained several warmer vintages that have confirmed that impression.

In that same year, Bailey Williamson, a former chef, took over the winemaking, and his steady hand has helped lift both the quantity and quality of the wines over the past decade at Blue Grouse. He was also very instrumental in coordinating the Cowichan Valley’s Sub-GI application. The second Blue Grouse change came in December 2022 when the winery was sold to a group from the same Jackson family that had purchased Unsworth. Similarly, the core management team, including Bailey Williamson, remained in place with available resources and industry experience.

Change in Climate or Kinder Vintages?

Some Cowichan Valley winemakers would say that before 2010, the good, riper vintages were running about 3 out of 10 emdash period vintages, such as 2006 and 2009 stood out for pinot noir in the valley. 2010 and 2011, however, were cool, rainy and challenging. 2012 was warmer and kinder, but the next three, 2014, 2015 and 2016, were warmer again, allowing the pinot noirs to demonstrate their real potential.

The degree days and other meteorological measurements may have been only incrementally better. Still, the wines were noticeably richer and deeper in flavour, with Cowichan Valley pinot noir notes of black fruits, forest floor, mulberry and more. Other factors were also in play, of course. Still, this trio of riper vintages was an essential boost to pinot’s profile and understanding of the potential for pinot noir in the Cowichan.

The Final Product

Spurrier’s last and perhaps most important “P” is about the product. Over the last decade, more and more wineries are making better and better pinot noir and are doing it more often. Global recognition has shown that Cowichan Valley pinot noir is not just a local hero; it can compete favourably with pinot noirs worldwide. The quality of the wines and the momentum of the grape is not likely to diminish. Passionate, skilled winemakers are hard at work trying to unlock the enormous potential of this particular piece of dirt. Expect the volume of pinot noir wine from the Cowichan to mushroom over the next three to five years. More wine to sell should result in broader distribution and growing attention, or precisely what a Sub-GI should be about.

In Summary

With vine age at 30 years in places and warmer vintages allowing greater grape expression, the question is, has an overall pinot noir style emerged from the Cowichan Valley? That remains to be seen because the sample size is so tiny. Results have been up and down, reflecting the variations in elaboration techniques, available clones and rootstocks, and a small sample of vineyard sites at three to four percent of B.C.’s 540-hectare pinot noir total. What we have seen among the many misses is some inspiring hits, and that knowledge gives us big hopes for the Cowichan.

There are, however, some differences between Cowichan Valley pinots and those from the central and Northern Okanagan Valley. Overall, Cowichan Valley wines are lower in alcohol, higher in natural acidity, less exposed to oak in the winery and show a more layered transparency of focused fruit that evokes the lighter end of Oregon pinots. The fruit profiles differ slightly, with central Okanagan pinots generally showing primary cherry, and strawberry notes and wood-influenced touches of vanilla and baking spices. North of Kelowna, the wines increasingly display “soprano” red fruits like cranberry, chokecherry, pin cherry and fresh pomegranate. Cowichan Valley pinot noirs, on the other hand, show savoury blueberry, blackberry, mulberry, marionberry and other lighter-berry fruits, as well as a note of wet forest floor richness. The more delicate touch of oak in the Cowichan Valley also seems to result in finer-grained, less robust tannins than their Okanagan Valley counterparts. They are all a work in progress.

quicksearch

quicksearch