April Fools’ Day, 2015.

It would have been easy to think that British Columbia’s main beverage alcohol retailer – the government-owned and operated BC Liquor Distribution Branch (BCLDB) – was playing a joke, by fundamentally shifting the way liquor was purchased, sold and priced in the province.

As of April 1, 2015, no one, not importers, agents, private wine store owners, restaurateurs or consumers, knew what to expect with alcohol prices. That day marked the division of the BCLDB’s wholesale and retail operations, the largest transformation in the organization’s 95-year history, and a move which was designed to put all liquor retailers, including the government-owned and operated BC Liquor Stores, on equal footing. “Levelling the playing field” became the government’s rallying cry throughout the process, one that began publically in 2014 with the Liquor Policy Review.

Concluding in November 2014 and after consultation from the public, the report contained 70 recommendations to modernize liquor sales in BC. Some of these changes have been implemented relatively easily and positively, including allowing local wine and spirits to be sold at farmers’ markets.

The second phase of the process has not been so smooth. As of April 1, 2015, all shelf prices in the BCLDB were moved to pre-tax pricing, with the majority of private retailers forced to follow. Under the new wholesale pricing model, the retail division of the LDB now purchases product at the common wholesale price from the wholesale arm of the LDB, exactly as privately owned stores must. The wholesale arm sets the markup, using a sliding scale that is not released.

This means that wineries and importers selling product to BC cannot calculate exactly what the after-tax (post mark up) price of the product will be. Government-owned LDB retail stores must now devise their own profitability decisions based on the same baseline cost of goods as a private retailer. Private liquor stores, owned and operated by citizens of BC, have become direct competitors to the retail division of the LDB. And though the LDB’s Retail Division and Wholesale Division are now separate, both report to the same general manager, Blain Lawson.

Wine is booming

For many years, wine sales have been strong in British Columbia. Canada’s westernmost province has long enjoyed strong Pacific ties to California, and has supported its own Okanagan Valley-centred wine industry. The city of Vancouver is also the golden gateway to the Pacific Rim, where an influx of investment money from Asia is fuelling development.

The province’s liquor system is overseen by two governmental bodies. The Liquor Control and Licensing Branch (LCLB) is responsible for regulating and monitoring the industry. The BCLDB, on the other hand, is responsible for purchasing, importing and distributing alcoholic beverages through the province, through their 196 government liquor stores, operating under the name BC Liquor Stores. The buying power of the LDB is undeniable, with four category managers responsible for product selection for millions of people. The organization oversees two types of sales operations: the retail channel handles sales from the BC Liquor Stores to retail customers directly, while the wholesale channel handles sales to resellers of liquor – the private liquor stores, restaurants, pubs and duty-free stores.

In addition to the government-owned BC Liquor Stores, there are approximately 670 private liquor stores operating throughout the province. A fixed number of licenses creates a high-stakes buying and selling game for their resale (going for anywhere from C$450,000 to C$750,000 ([$338,000 to $564,000) per license). The private liquor stores have been instrumental in growing the wine culture of the province, especially in Vancouver, where the sommelier and wine trade community thrives through education and collaboration. Unlike the unionized government stores, the independently operated private liquor stores have the opportunity to hire who they want (interested, engaged sales force) and are able to select the products from the BCLDB and via local agencies that suit their goals and clientele.

One benefit of the government overseeing all liquor sales has been the reporting mechanisms available. It remains to be seen what will be made public knowledge post April 1, 2015, but the transparency of sales and quarterly market reviews up to that point were useful tools in tracking liquor sales in the province. Provincial liquor sales were C$3.1bn in 2014/15, which was C$120.5m or 4.1% percent higher than budgeted and C$148.8m or 5.1% higher than the prior year. Of this C$3.1bn in total sales, C$1.03bn were wine (an increase of 7.1% or $68m); $1.1bn were beer; C$772m were spirits, and C$168m were refreshment beverages.

The rise of wine sales is relatively recent; BC consumers traditionally preferred spirits and beer to wine. But wine sales are growing to the point where they now eclipse spirits and are approaching beer. There are currently 24,465 wine listings in the BCLDB’s wholesale system. Over the last year, 17,911 have had sales transactions, meaning they are actively being sold.

During the fiscal 2014/2015 year, the customer count at the government-operated BC Liquor Stores increased to 36.4m from 36.2m customers and the average retail customer transaction value increased to C$33.46 from C$32.90.

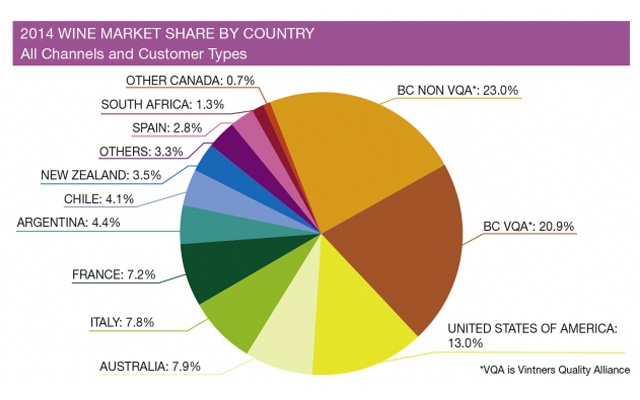

From March 2014 through March 2015, almost all of the import wine categories grew, except for sparkling wine which saw a 15.02% decrease in retail dollar sales. White wine was the strongest category leader, growing by 5.99%, followed by rosé at 4.03%, red with 2.02% growth, and the aperitif, dessert and fortified category growing by 0.24%. As in past years, the US leads the import category by market share, followed by Australia, Italy and France.

Looking ahead

Though much has been said about “levelling the playing field”, the slope is still steeply slanted to benefit the BCLDB. The government stores remain the only outlet that can sell to restaurants and other members of the hospitality industry. Prior to April 1, 2015, government stores paid BCLDB’s wholesale price, which was less than half of the final shelf price. Under the new system, government liquor stores will pay the same as private liquor stores, a sliding scale that approximates to roughly 16% less than the final shelf price. If shelf prices are kept the same, these stores will be operating on margins that are very close to their operating expenses, reported at 17.5% of actual sales in the 2014/2015 Annual Service Plan Report. How the government liquor stores are planning to be sustainable in the long run, and how private stores are expected to follow suit and thrive with these margins is unclear.

As part of the Liquor Policy Review recommendations revealed in November 2014 was the announcement that qualifying grocery stores will be permitted to sell alcohol as of April 2015. To date, that still remains a cloudy, contentious area, with the number of grocery stores in the province able to meet the set regulatory requirements limited to nearly zero. In addition to the moratorium on new liquor licenses in the province, geographical and store size restrictions and a surprise decision to restrict liquor sales to solely BC-produced wine, the restraints appear ready to burst open at any time according to Mark Hicken, a Vancouver lawyer specializing in wine law. Hicken points out that “a preferential treatment to BC-produced wines does not appear to be trade compliant with Canada’s obligations under both NAFTA and GATT.” There have already been letters from both the California Wine Institute and Wine Australia expressing their concerns to the BC government and urging a swift reversal to the BC wine-only model in grocery stores. According to Hicken, “in similar markets and models (to ours) in the United States, up to 70% of all alcohol sales take place in grocery stores. It will be difficult to maintain these types of restraints for the long-term, legally. They are bound to collapse.” He predicts open grocery shelves to all international products in BC within a few years’ time, changing the liquor retail map dramatically.

For Anthony Gismondi, one of Canada’s most respected wine journalists, the changes since April 1 signal “a race to the bottom”. “There’s an abundance of caution by people in the industry right now across the board – from wineries to agents to importers to private liquor store owners. When people get nervous, they are constrictive.” His fears echo that of many private wine store owners interviewed for this article, who wished to remain anonymous. “With such slim operating margins, the BCLDB seem bent on destroying private-sector shops,” Gismondi muses. Stores, including the government’s own BC Liquor Stores, will have to look at creative methods for making profits, including private-label branding, a tactic long favoured by supermarkets outside of Canada. “Big companies and large brands will benefit, the ones with the budget to bring in exclusive container loads of cheaply priced juice, repackage and sell for a large profit,” he predicts. For him, as for many, the potential loss of wine culture in a province that has built one of the strongest food and wine communities in North America is a case to consider.

This article appeared late last year, in Issue 6, 2015 of Meininger's Wine Business International. To find out who the relevant buyers are, click here.

quicksearch

quicksearch